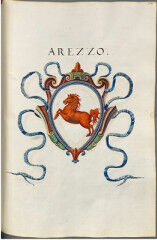

This piece will be a brief dally away from our wine and food focus, as we take a look at three favorite sons of Arezzo. Just a quick backdrop before we delve into the lives of these three geniuses:

Born as an Etruscan outpost, the town thrived under Etruscan and Roman rule (called Aretium during Roman times). However, this thriving culture was not destined to remain standing, succumbing to a similar fate as other Tuscan centers when falling under the domain of the Goths as they destroyed the Roman capital in 476. In the 8th-10th centuries the area was slowly but surely building itself up through blossoming social, political, military and architectural developments. Likely thanks to these improvements, the walled, prosperous comune was too enticing for the Florentine to pass up on, and in the 1320s, the city fell under the permanent domination fo Florence.

Even while tremendous constructions and works of art and literature were crafted here, the city’s political, military and economic autonomy was under the thumb of different external rulers, from the House of Medici to the House of Lorena(until 1870).

Let’s now take a closer look at the three prodigies of Arezzo, given our knowledge of the historic moment the city experienced.

- Piero della Francesca, one of the four cardinal figures of Renaissance painting. He was not actually a native son, being born in the neighboring San Sepolcro and ending life there as well, but thanks to his tremendous artistic output, he’s intimately associated with Arezzo. Perhaps della Francesca’s most admired work can be found in an apse of the church of San Francesco. Here you can take in the tremendous cycle of alfresco paintings Story of the Holy Cross, unfortunately partly damaged by neglect in 1600-1800 and by clumsy restorations’ in the 1850’s. When visiting, be sure to bring along binoculars to ensure you take in every single detail.

- Giorgio Vasari instead was a native son, born in Arezzo in 1511, dying in Florence in 1574 while trying to embark on a final departure for Arezzo. The three-day journey over steep, pot-holed, rocky and winding roads would be unthinkable to us today, but Vasari was so devoted to his birthplace that he undertook the attempt to return all the same. Vasari is remembered for many architectural and paintings in Florence, Rome and Arezzo, among them the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and the stupendous loggia of Piazza Grande in Arezzo.

Vasari’s perhaps finest work however is his written masterpiece, “Le Vite dei Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori ed Architettori, (The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects) written and first printed in 1550, then reprinted posthumously with his annotations and corrections in 1588, and innumerable times in multiple languages throughout the world. This work of a lifetime, together with his well-preserved and hefty correspondence with select notables of the time, offers more penetrating insight into the arts and daily existence of the Cinquecento than any other single source. The Lives, available in Penguin paperbacks, make lively, often page-turner reading. Giorgio Vasari was undoubtedly one of the most creative and influential men of his time.

- Guido Monaco, also known as Guido the monk, was born in Arezzo in about 990, ending life there as well. Guido is known throughout the musical world as being the founder of modern musical notation. While the notes of the basic scale are C, D, E, F, G, A and B in the Anglo-Saxon cultures, among speakers of Neo-Latin languages (Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian) including Latin-Americans and Asians and Africans, the notes instead are Do (originally and still in French, Ut), Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La and Si. These notes exist thanks to Guido’s imposition of tonal order. Guido taught his choirs to intone the correct intervals according to the first syllables of the first six lines of Ut quaeant laxis, a universally known Latin hymn.

The first words of each line are Ut, Resonare, Mira, Famuli, Solve and Labii (si was added later). Guido also invented the four-line staff, enduring through Bach’s time, and the various key signatures by letter, so that the tonal intervals of a melody could be written, transmitted and read with certainty, eliminating the need for oral transmittal via living messenger. Although German musicians gradually switched to the names C, D, E, for a variety of reasons, the rest of Guido’s system has survived, with modifications as needed to suit the times. Even though it’s possible that his inventions would have arrived eventually (even through another figure), the fact remains that every piece of music we’ve ever heard has been preserved by the genius labors of Guido the monk of Arezzo, nearly 1000 years ago.